How I Remembered the Kanji

I have some big changes coming up, most notably I’m moving to Japan this month!

In preparation for that I undertook a tremendous task, learning the kanji, the many Japanese characters that present a huge hurdle for westerners. Specifically, I wanted to read and recall the meaning of the 2273 most common kanji in the language, and here, 6 months later, I can do that! I’m really proud that I was able to complete my goal and I’d love to share some interesting parts of that journey. Read along, if you’re interested.

Why?

Six months ago, I was a beginner level in Japanese. Today, I still am a beginner, despite all this work. The obvious question is, why focus on kanji before other things? Learning so many characters is not immediately useful, and furthermore it’s well known that without practical, repeated use words are easily forgotten, leading you back to square one!

Well, first off, kanji was a big personal hurdle for me. Playing a game or reading an article, I would almost immediately be stopped in my tracks. Unable to comprehend I’d be jumping into a dictionary constantly, only to forget what I learned by the next day.

I was intrigued upon finding that many self-studiers used a specific, mnemonic-based approach, optimized for adults, to learn the kanji much more quickly than even native Japanese speakers did as children. Could I make my future learning easier by getting over my biggest obstacle first?

I also observed that focusing on kanji while in the US would give me more time to communicate and immerse myself once I reached Japan. It’s one of the most tedious and unsocial parts of learning Japanese, mostly spent reviewing in a book. Why not get it under my belt before going to Japan?

The final and biggest reason to learn was for motivation. I was in a down emotional state, unsatisfied with my professional situation, as well as Covid blocking my other goals, and here I was deciding to drop everything in my life and study in Japan. I needed to prove to myself that I would spend my time there valuably, and I needed a BIG win to do that. I knew that after investing so much time into an activity, I wouldn’t quit. I can’t waste this much time for nothing.

So that was it. I HAD to get through this!

By the way, if you want more information about learning kanji first, check out a blog post from Matthew Hawkins, Nick Hoyt in Japanese Tactics and an article from James Hesig, writer of Remembering the Kanji, the book I used during my study. These resources explain better than I can why it’s worth considering. Also, more on Spaced Repetition, which is a pretty fundamental brain concept that applies much further than Japanese or languages.

What is a Kanji?

A kanji is a character with one or more meanings and one or more readings, depending on its context. A Japanese child learns the standardized Joyo Kanji list of 2,136 characters in 12 years throughout grade school through classic teaching methods and repetition.

度

This character by itself means “degree”. The character has 5 possible readings/sounds when combined with other characters, and it is part of over a dozen different words. For example ご法度 means “contraband”. It also has a specific number of strokes, and order and direction that each one must be written. Can you guess the correct stroke order of this character?

Here’s another word made up of two kanji.

綺麗

Prior to my studies I was stunned by this web of lines and markings. That second kanji alone looks like it would take a half a day to remember, let alone in context.

As it turns out, this just means “beautiful”, pronounced kirei, but its written form is simply impenetrable for a beginner. In a traditional classroom, I would first learn to read words in hiragana, an alphabet like in English (きれい), but any Japanese article or sign written for adults would use kanji and I’d be stuck in the dictionary again.

As you can see, reading and writing can be a pretty daunting task! Fortunately, while the Kanji are not necessarily intuitive, they are logical, in ways that I will explain below.

The Goal

My intention was to recall and be able to write (but not speak) 2273 Kanji based on key word meanings. This number of Kanji comes from a crafted list called HeisigLite+.

HeisigLite+ is an optimized list, it very simply takes the top most common 2000 characters used in newspapers or magazines (note the or, it takes the union of those), resulting in 2273 characters. This set, other than 19, are included in the 3000 characters from Heisig’s Remembering the Kanji (RTK), which is the book that pioneered this Kanji study approach. So basically, I used a consolidated version of RTK.

Once I could recognize the kanji, I could focus on saying and using them. Yes it’s true, you can’t learn the entirety of Japanese in just 6 months, but this was a practical beginning.

Where I Started

We’re almost to the actual process, but I want to throw out some disclaimers of exactly where I started out on day 1 of my attempt.

I’ve lived in the US up until now and have never taken a Japanese class. Since my wife is Japanese I have been exposed to the language for nearly 10 years through subtitled Japanese movies, numerous vacations to Japan, and interspersed, half-hearted attempts to get past beginner level. I even tried to get through Remembering the Kanji twice before, each time learning a couple hundred characters only to give up and forget them completely (ouch!).

That said, on day 1 I wasn’t even comfortably able to write the Hiragana and Katakana alphabets (used for grammar, loan words, and in place of kanji in some instances), and I didn’t know enough vocabulary or grammar to pass the easiest Japanese fluency test (the JPLT N5). So, despite my best efforts, I would have been considered a well-intentioned but absolute beginner in a second language school.

The Process

I used a combination of tools to learn.

Remembering the Kanji, volumes 1 and 3, by James Heisig

Anki, specifically AnkiWeb/AnkiDroid

HesigLite+, a card set for Anki

I used the HeisigLite+ list because in my previous two attempts I’d started with RTK, but found some of the characters were pretty much useless. The HeisigLite+ list was the balance of completeness and usefulness that I was looking for to base my studies on.

My daily study consisted of two parts, review kanji due for recall, and learn new kanji.

For recall I used Anki. Anki is a general purpose spaced-repetition flashcard program with some handy tools like syncing on my PC and my phone so I can study anywhere. I see the key phrase that I have associated with the kanji and try to recall the kanji.

If I remembered it correctly the program extended the next recall period. This is based on the Spaced Repetition principle that in human memory, successful retention increases the time needed for the next recall. If, on the other hand, I forgot the kanji I would have to restart its recall period all over.

At the end of the review session, I’d see how I did. Here’s a simple summary of one day of review.

For the learning portion, I would open up the HeisigLite+ flashcard list in Anki. I generally learned 20 new kanji in a day, occasionally more, or less. I would then reference Remembering the Kanji for information/hints on how to remember it and to check stroke order. I’d also reference Jisho, an online Japanese dictionary, when needed for more detailed stroke order, or additional context.

It’s a repetitive and straightforward routine, but how is it possible not to forget?

Making Up Stories

To learn each new kanji, the most important part was developing its mnemonic story.

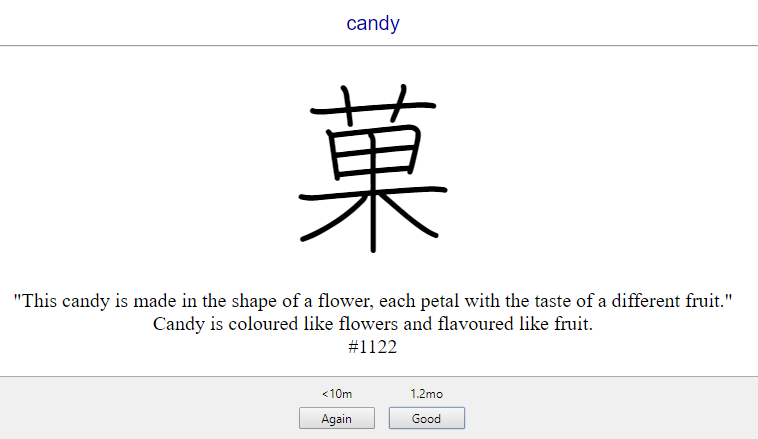

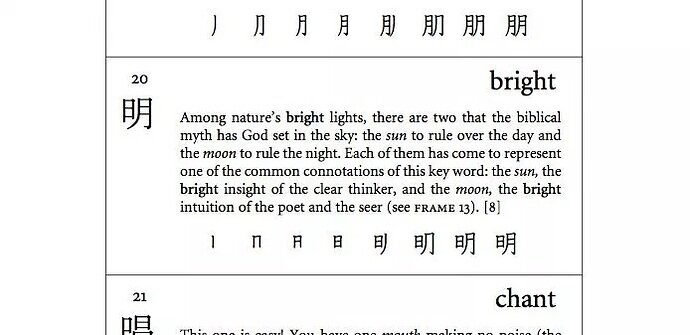

An example mnemonic in Remembering the Kanji

It may sound abstract if you’ve never attempted this (it definitely did for me), but my goal was to write as vivid and unforgettable a memory into my mind, with visuals, sounds, smells, or anything else that a real-life memory could contain.

Both the existing HeisigLite+ flashcards and RTK have example stories for inspiration, but at the end of the day making the story stick into your memory is unique to you.

While studying I learned many nuances of my own recollection, what stuck and what didn’t, and by the end most of my stories were embellished with images of my friends, family, and other experiences from my own life. The kanji strangely became a doorway to another dimension, a series of narratives in some supernatural universe that I was connected to by threads.

The characters in the stories are the radicals, common sub-components in different kanji, often with unrelated meanings. RTK groups kanji together by radicals to make stories reinforce each other and build up stroke knowledge through commonality.

A perfect example of this are the radicals that Heisig calls the taskmaster and the running legs.

攵 vs 夂

At first glance these might look identical, but they aren’t. The first has 4 strokes and the second has 3 strokes, and the subtle difference in appearance can actually completely change the meaning of the kanji they are in! While the immediate similarities are obvious, Heisig cleverly gives them very unique meanings in the stories, so when I see these elements in my own stories, they have no relationship to each other. For this reason I never mix them up.

In some cases, seeing a similarity between the written forms CAN strengthen memories of similar radicals. I was able to take advantage of both similarities and differences when remembering.

After developing my story, I’d write the character at least once (sometimes more), and once I’d completed my daily 20, I would move their flashcards to the Anki review list and quickly complete them.

Anki by default actually mixes new and existing cards, but I found that studying the new cards separately was actually resulting in better retention. Reviewing right after learning helped solidify my new stories and clear up any issues. This was one of many small tweaks I did to individualize my routine.

Writing

When I had first tried to learn through RTK, I felt like writing was impractical knowledge. Who needs to write kanji and remember strokes in this technological day and age? However, Heisig strongly recommends writing, claiming that it “kills two birds with one stone”, so I humbled myself and tried. It turns out his assertion is absolutely correct.

Writing helped my retention and story building immensely, as well as seeing potential confusion early while clarifying the stroke order of difficult kanji. As a result, it’s fair to say that I got my writing skill for free. It made up the time spent with all its other benefits.

Not to mention, now I get to marvel at the volume of characters I learned!

How Did It Go?

My goal was to keep studying every day until I finished. Reading some articles online it seemed like people generally finished this in 3-4 months.

I don’t enjoy forming habits, I don’t like waking up early, and I HATE studying. As time went on, I realized that 3 months was impossible for me. My goal had been to learn at minimum 20 new kanji a day, but reviews kept getting longer and longer. I had a full time job, a wife, hobbies, friends, family, and a goal to learn the other aspects of the Japanese language. I couldn’t just spend 8 hours a day, 7 days a week reviewing kanji!

I would need a cadence and a strategy to be able to complete this monumental task. What I found after a few weeks was that I could consistently do one hour and 15 minutes: 45 minutes for review and 30 minutes of learning. This meant extending my completion date, I would have to prioritize finishing reviews over adding new kanji.

Review time over the entire duration of study

Around 15% of days I was forced to skip learning to keep up with reviews. Even a single day slip up would result in a huge review stack, costing me 2 to 3 hours the day after. My biggest fear was creating a nightmare 5+ hour backlog of review catchup. I could easily burn myself out trying to reach the finish line at an unrealistic pace!

By taking my review backlog very seriously, I was able to maintain my cadence, and finished right on target with an average 45 minutes a day of review.

Getting To 75% Done

My lowest point came around the 75% mark. As my review intervals got longer and longer, my retention started getting worse, which was really frustrating. What point is there to learn new kanji when I can’t remember the old and supposedly mature ones? Will I just forget all these kanji after all? Can these all even fit into my brain?

Doubts and frustration increased, but I forced myself to look at things outside of my mental state. Even though my retention was getting worse, I could see from the data that I was still over 80%, which meant I would be able to use this knowledge in practice. 80% of 2000 kanji is still a lot of kanji.

I was also encouraged by my native Japanese friends, who shared that even they would occasionally forget kanji and couldn’t write some complex kanji without help. Perfection was not important or realistic and my time was producing results, even if they weren’t as great as I wanted. I would just have to keep going despite the pain.

I added daily vocabulary and grammar to my study routine. My Kanji level was high enough that I was no longer getting blocked by it, and recognizing the kanji I had learned in vocabulary became a source of excitement. My kanji knowledge started to augment my other studies rather than hinder it, so working on vocabulary in itself became a great motivation to keep reviewing.

Memory

What I learned through all this was that context is the key to memorization.

I have a terrible memory. If there was an objective memory test, I would score very poorly, as I’ve observed my memory is significantly worse than my peers.

Kanji isn’t well suited to rote memorization techniques due to their confusing similarities. The unique stories I made are a vivid dimension that holds connections between different radicals and different kanji. The stories are flexible to be expanded, augmented, reinforced, and strengthened over time.

Around the 1400 kanji mark I came to a startling realization. Story building and spaced repetition was making it impossible NOT to remember the kanji, despite my weak memory. It taps into the fundamental workings of recall that are universal to human minds. Some days I felt like I couldn’t remember much of anything, and I believed I would fail. Yet as time continued, I was extending my recall even for the most tricky characters. It was slower than I wanted, more difficult than I wanted, but it worked. It really worked.

The kanji have accelerated my general Japanese abilities because they are an underlying layer that connect ideas. There’s some similarity with Latin roots in English, prefixes and suffixes. Building that web of related base information is what I had hoped would be the result of all this work, and it worked.

It’s clear to me now that context is integral to traditional study methods as well. Learning a group of new vocabulary, doing practice speaking, learning key example sentences, or simply watching Japanese TV shows and writing about them, all build connections and strengthen memories, allowing people to retain thousands or tens of thousands of words.

Something I did not expect was I became fond of my kanji memories. The more ridiculous and funny the stories are, the more unforgettable the memories, so I chuckle a little whenever I see certain kanji with great stories.

Some Interesting Statistics

Kanji added/learned: 2273

Duration: 6 months (to the day!)

Review time: 8228 minutes

Expected kanji/day: 20, actual: 12.22

Days studied: 97% (182/186)

Learning retention: 85.45% correct

Young retention: 89.70% correct

Mature retention: 88.95% correct

One note on retention. I didn’t penalize myself for stroke order mistakes and used the “hard” answer in Anki rather than “again” more as time went on for minor inconsistencies. That worked for me, and while it means my “actual” retention is lower, I think I did a good job following rules that favored my goal of kanji recognition over a statistic.

I find it funny that my learning plus review time totaled 228 hours over those 6 months, yet in the same amount of time I played around 200 hours of the video game Escape from Tarkov. So for all my humming and hawing about how difficult the time investment was, I played video games almost as much! Time sure flies when you’re having fun, but stands still when you’re studying.

All in all, it was a great return on time invested.

The Best Method

I have one more thing to rant about for any people out there learning a language, especially those who like to “work smarter, not harder” like me, something that came from my numerous past failures. Heisig’s Remembering the Kanji worked for me, not because it’s the best way to learn, but because I felt engaged by the method and focused on progress.

Looking for better ways to learn is addicting. It can inspire but eventually it has diminishing returns.

Languages are frustrating in their immense requirements of time and willpower. They are massive dumps of information, exceptions, and gotchas, with no central architect. They can’t be outsmarted with ingenious shortcuts because dedicated effort just works better for its class of problems.

I succeeded when I made a long term commitment to a goal and stopped searching for more interesting methodologies.

Was It All Worth It?

Yes, it was.

I still have many kanji reviews to do, and a world of grammar and vocab, but I conquered the mountain I most feared. When I watch Japanese TV, I see all characters everywhere I recognize, and I use them to build up and remember new words. Best of all, I know I will spend my time wisely when in Japan. I have full confidence that I can take advantage of my time immersed in Japanese and continue forward.